About that decision you made that others viewed as excessive…let us help you.

I had the opportunity to talk with a senior executive struggling with her relationship with her leader who was constantly correcting minor errors, spending inordinate amounts of time on small details in her project plans, and most recently, her leader took over a cross-functional meeting she was delegated to lead. The reasons for this “hostile takeover” (my words, not hers) were that the materials were not strong and the meeting was high stakes. In short, her leader was engaging in overcorrection.

Due to these interactions, this senior executive reported feeling a decrease in confidence, motivation, creativity, and initiative while working with her leader. Currently, her engagement with her leader and her team seems more stressful, and she feels trust dwindling with her leader. She is questioning her skills and talents and is considering leaving her job because of the situation.

So what is overcorrection, and what are its effects? Why do leaders do it? What should leaders do instead?

When a leader responds to a mistake, problem, imbalance, or concern by taking a bold action, seen by many as excessive, and resulting in the creation of new problems, complexities, and issues, we call this an overcorrection.

Now, I want to be clear, there are times when a bold action might be necessary: when a team member has experienced harm by another team member’s behavior, or the safety of the team or the organization is at risk, or an organizational culture vacuum appears as a result of a change in people, strategy, finances, and/or processes, to name a few. I would not call this bold action an overcorrection but instead would call those instances explicit leadership.

For our purposes here, a good “lookfor” with respect to an overcorrection is when the bold action a leader takes results in substantive harm to a team’s confidence, creativity, initiative, and culture.

I can recall a time when I also committed an overcorrection with my direct reports in preparing for a professional learning sequence for a large group of teachers. I was new to my role and wanted to show folks I knew how to host a high-quality, high-impact professional learning series. After providing several feedback sessions to my team about the arc of learning, the outcomes, and the designs, I realized I just needed to “do it.” Time was running out; my team did not understand what I wanted; and we needed the series to go well. At that moment, I felt personally responsible for the errors and volume of feedback I was giving them.

For my team, I found out later, they were devastated.

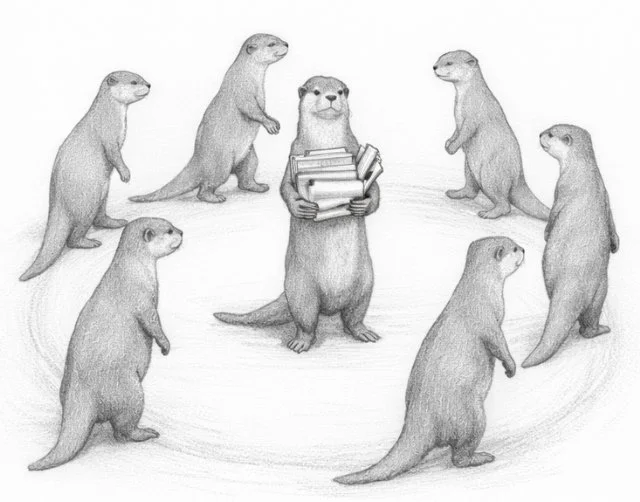

Can you picture it?

Me, taking over and holding all the tools. My team, circling me, in motion, but carrying nothing.

My response to this problem was truly disproportionate to the actual challenge in front of me. Honestly, the error my team was “committing” was really my error. I learned too late that they lacked the expertise to execute the professional learning session, and my criteria for success were a mess (more on that in a future newsletter). I thought they could do it, but they were not ready to dream up, design, and implement the session arc I needed for our teachers. I made this situation worse by holding onto the work of my team much longer than I should have. This was their work to do, and I took it from them. And I did not give it back.

Unfortunately for my team, I had too many experiences sitting in professional learning that was terrible. I did not want to contribute to a similar failure. As a matter of fact, I feared joining the ranks of past failures. I wanted better training sessions for our teachers.

The solution I came up with (i.e., research, design, implementation, and follow-up all done by me) was way too complicated and actually created additional opportunities for failure. I could not do all that was required. My team did not learn the content or the delivery. My team also did not contribute to future content. They literally stopped contributing. We would sit in meetings, and they would just look at me and say, “what do you want to do?” No initiative, no creativity. I would give feedback to them about how I wanted them to take initiative and bring ideas to the table, and their response would be, “Thank you for the feedback. I will remember that for next time.” But the next time was the same as the last time. I felt overwhelmed, tired, and completely confused. I realized I had made a huge mistake. Our team was in motion, but we were making no progress.

An organization can also contribute to this type of behavior from a leader. Organizations rich in pressure to be perfect, prioritizing complex solutions and project plans over results and people, constantly changing the success criteria, and/or chasing the newest, shiniest initiative, all create the conditions for leaders to engage in overcorrection.

I went wrong in about 100 ways. Three big ways I went wrong and why include:

I did not articulate clear criteria for success. My team was guessing what I wanted. And they repeatedly guessed incorrectly. Why did I do this? Read the next one.

I misunderstood the knowledge of my team. My brilliant, talented, committed, driven, and collaborative team did not have some key background knowledge they needed to complete the project. This is of no fault of their own, and ultimately, it was my responsibility to make sure they got that knowledge. I just assumed they had it because they were brilliant in so many ways.

I underestimated my response to my team’s work. I felt pressure to deliver on something amazing. I did not realize how much pressure I put on myself until my team was not performing the way I wanted them to perform. My response was abrupt, primitive, and went against the ways I wanted to interact with my team.

What should I have done instead?

Stop and reset. I should have taken time to stop, reflect, and be more explicit, sharing with my team a clear criteria for success. If I didn’t have one, I should have told them I didn’t and co-created the criteria with my team.

Get proximate. After doing the first step, I should have joined their next planning meeting, providing guidance and affirmation and ensuring alignment back to the success criteria we outlined in Step 1. I should have also articulated what was a priority and what was a nice-to-have as we are planning the project - recognizing that we were on a short timeline between planning and execution.

Let them lead. This was critical. I should have insisted that my team execute the project with my collaborative support, encouragement, and guidance. They should have been out front, not me.

Spend time in a retro/debrief. When the project ended, I should have made time for our team to engage in a retrospective of the project and our processes. What did we do? How did we do it? What did we learn? What do we want to keep, change, and discard? Most importantly, we should have stamped our learning and integrated it into future projects.

Although these steps may seem like they are going to take quite some time, there are some hacks to use, e.g., come to the meeting with criteria set and ask for feedback; share what is a priority and what we can let go; let them lead the execution; engage in a retrospective over the course of a few days; not in one long event. These are just a few adjustments to ensure the spirit of the change can occur, even if the context for the change is complicated and feels unwieldy.

As always, this section is about unlocking/disrupting your thinking. As you read, think about the ways in which your current models of leadership are serving (or not serving) you well!

Stories from the the Orchard: Pruning Shears

In the orchard, fruit did not grow by accident. Each tree needed the right angle of light, the right cut at the right season, and patience from the gardener, Riley.

For years, Riley believed patience meant doing the pruning himself.

When branches tangled, he reached for the shears and made the corrections. When fruit grew unevenly, he corrected its shape. When a storm threatened the harvest, he worked through the night alone, certain the orchard’s success depended on his precision, diligence, and constant correction.

The trees responded to Riley by waiting.

They leaned where he leaned them. They grew only where he directed. When asked to stretch toward the sun, they stayed still, unsure which way was right. Each tree in the orchard looked busy, but Riley’s harvest constantly yielded little. Riley reflected this mismatch of effort and the orchard’s production.

One morning, exhausted from the work of tending to the orchard, Riley decided to change his strategy. He decided to leave the trees alone and just notice what was happening.

After a few weeks, Riley did notice something he had missed: the trees were not weak. They were untrained. They had never been shown what “healthy fruit” truly meant—they were only corrected when they fell short.

So he changed his work–again.

He stood amongst the orchard, marked the ground, and announced to his trees: “This is what strong growth looks like.” He traced the arc of light, named which branches mattered most, and which could wait. Then he stayed nearby—not with shears raised, but with questions and quiet guidance.

Most importantly, he stepped back.

The trees bent. Some bent awkwardly. Some reached too far. Riley resisted the urge to intervene. He let them learn the weight of their own branches.

At the end of the season, Riley called a pause. Together, in the orchard, Riley and the trees studied the harvest—what worked, what didn’t, what they would keep, change, and discard.

The orchard transformed. The yield was stronger.

Not because Riley worked harder—but because he finally shared what success looks like, offered support, and let the trees grow more fully.

Applying the Learning - A Case Study: The Senior Executive Presentation

Elena was a respected senior leader known for her strategic thinking and calm presence in high-pressure situations. When she was asked to lead a cross-functional initiative tied to an executive audience, she approached the work with care. She drafted project plans, coordinated stakeholders, and prepared materials for a critical meeting she had been explicitly delegated to lead.

Her manager, David, was deeply invested in the outcome. As deadlines approached, his involvement intensified. He flagged small formatting errors, rewrote sections of Elena’s plans, and questioned minor sequencing decisions. Each correction came with an explanation: the work was high stakes, expectations were high, and mistakes could not slip through.

The day of the meeting, during a full team meeting, David announced that he would step in to run it himself. He explained that the materials were not strong enough and that it was safer for him to take over. Elena sat silently, taking notes on a project she had designed but no longer owned. The full team watched the situation unfold in real time.

Afterward, Elena noticed a shift in herself. She hesitated before sharing ideas. She waited longer to act. Her creativity narrowed to what felt “safe.” The full team picked up on this change. David started to notice how team planning meetings became quieter. Specifically, he noticed how Elena’s initiative slowed. When David asked for new ideas, the team asked clarifying questions instead: “What are you looking for?” “What would you prefer?”

David felt increasingly burdened. He wondered why Elena and other members of the team seemed less engaged and why progress required so much of his direct involvement. From his perspective, the project was moving—on time, polished, controlled. From Elena’s perspective, and many members of the team, something essential had been lost.

Privately, she questioned her readiness for leadership at this level. She wondered whether the problem was her skill, her judgment, or something harder to name. She began considering whether staying made sense if leading meant having work taken from her when it mattered most. Late at night, she browsed job postings—not because she disliked the work, but because she no longer trusted her footing in it.

The initiative continued. The results appeared solid to many. Yet beneath the surface, trust and capability were quietly eroding.

Case Study Reflection Questions

What might be contributing to the breakdown Elena is witnessing?

If you were David, what would be your next steps? If you were Elena, what would be your next steps?

How does pressure—for perfection, speed, or reputation—shape each leader’s response?

That’s it for this month! See you next month!!